Thinking Naively (and Breaking the Rules on Purpose)

Let’s ignore all best practices and architectural principles for a moment, and look at the software from a completely naive perspective. Sure, we could just write one big application that does everything — the monolith approach. No layers. No (micro-)services. No abstractions. Just one app to rule them all.

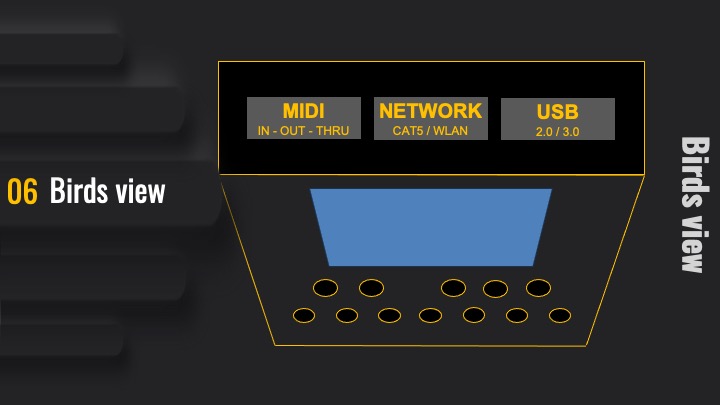

Our DIY pedal board consists of a few obvious components:

- Button Panel → for triggering notes, chords, and actions

- MIDI/USB/Network I/O → for external communication

- Touchscreen → for live control, feedback, and configuration

But lets assume Java is our hammer, every problem starts to look suspiciously like a nail.

JAVA

As a Java developer since version 1.8, I’ve been through my fair share of pain — from the awkwardness of EJB 2.0, to the madness of OSGi, and more than a few over-engineered frameworks that promised everything but delivered therapy bills instead.

For our “DIY-pedal board” MIDI can be handled easily by the javax.sound.midi package, and for USB access, there’s multiple cross-platform libraries like usb4java (http://usb4java.org/) — which wraps native USB access with JNI. On a low-powered device like a Raspberry Pi, you can even offload some work to the client via a fancy JavaScript UI, instead of rendering UI on the device, backed by a simple internal REST API. But I’ve opted for a 7-inch touchscreen on this board—and that changes things, because from a user’s perspective, a native UI just feels more responsive, polished, and frankly, more satisfying. And over the years I’ve used more UI libraries than I’d like to admit:

- XVT / XVTDSC (a cross-platform C/C++ framework, see: https://providencesoftware.com/products/)

- Turbo Vision and OWL (on Windows, back in the C++ days, funny: https://github.com/magiblot/tvision)

- Delphi, C++ Builder (Borland, now https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Embarcadero_Technologies)

- Xcode/Objective-C, list goes on…

JAVA - UI

And Java gives us several options here:

- Swing (https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/uiswing/)

- SWT / JFace (https://eclipse.dev/eclipse/swt/, https://www.vogella.com/tutorials/EclipseJFace/article.html#definition-of-eclipse-jface)

- JavaFX

But these days, JavaFX combined with SceneBuilder (https://gluonhq.com/products/scene-builder/) feels like the closest thing to drag-and-drop UI design since my time with Xcode. It’s fast to prototype, visually intuitive, and still plays well with the JAVA ecosystem.

Java has It all, at least on paper:

- MIDI handling

- USB access

- REST APIs

- Native UI capabilities

- A rich set of libraries (and decades of developer muscle memory)

SceneBuilder, GraalVM & The Path to Developer Despair

Creating a minimal SceneBuilder file and launching a basic JavaFX-based application was fairly easy — and honestly, it worked out of the box. Well… more or less. Booting it on the Raspberry Pi, however, was a different story. Even basic animations were choppy and stuttering, which meant we had to dive into:

- Hardware-accelerated rendering

- X window management optimization

And a whole category of issues I hadn’t expected to face this early in the project Still, I trusted the marketing hype behind GraalVM and decided to give native-image compilation a try.

Boom. The project exploded on Day 5.

GraalVM: Where Your Dependencies Go to Die

Turns out, GraalVM strips away most of the useful Java VM packages — including:

- javax.sound

- java.awt

And with that, we lost two absolutely critical components of the DIY MIDI Music Workstation Pedal board:

- MIDI support

- The UI

Perfect.

A bit of digging revealed that tools like Gluon offer support for native compilation with AWT alternatives,

and even include their own SceneBuilder builds for JDK 23 and 24.

But here’s the catch: Gluon VM native-image builds that actually support AWT and Raspberry are stuck at JDK 17.

And — you guessed it — SceneBuilder 23/24 can’t handle JDK 17 builds, JavaFX app can’t handle SceneBuilder 23/24 xml’s

and crashed immediately on launch.

DIY Fixes in Dependency Hell and native images

The only workaround? Clone the SceneBuilder source from GitHub, check out the 17 branch, and build it yourself. Manually. Because obviously, what Java developers love most is building UI design tools from source. And if you thought dependency hell was the worst experience a Java developer could have… you haven’t tried getting a natively compiled JavaFX app to work with agent-based runs, mysterious config files, and stack traces that read like ancient curses. This is, without a doubt, the most painful, time-wasting process I’ve endured as a Java developer (and I survived EJB 2)

When Java Isn’t Enough — Rethinking the “All-in-One” Fantasy While we managed to make some progress with workarounds, it quickly became clear that the all-in-one Java approach wasn’t going to cut it. Why? Because native Java MIDI support was still gone — and no amount of wrestling with GraalVM and others was going to bring it back.

Remember the Hammer and Nail?

Earlier I mentioned the “Java hammer / every problem is a nail” syndrome. Well, if Java can’t give us MIDI in a compiled image, maybe it’s time to stop hammering. So here’s the pivot: Instead of trying to shoehorn everything into one giant Java application, we offload hardware-near components (like MIDI and USB detection) to small, standalone processes. These components can:

- Run in a standard JDK runtime

- Communicate with the core JavaFX app over WebSockets or REST

- Avoid dependency hell while still giving us flexibility

Problem solved, right?

Wait — Why Stop at Java?

If we’re treating MIDI and USB as external, API-driven services, then why not go all the way back to the metal? Why not write these components in bare-metal C++, where performance is king and latency is low? After all, once we define a clean protocol and clear interface boundaries, the language behind each component becomes … irrelevant. So instead of trying to make Java do what it no longer wants to do, we build the system around well-separated modules, each written in the language that suits its job best.

- C++ for hardware handling

- WebSockets and REST for communication

- Loose coupling, strong boundaries

Sometimes you don’t need to force the nail. You just need a better tool.

A new Direction for the UI

And this brings us to the final (and perhaps boldest) decision: What if we drop the last Java component altogether? If JavaFX and SceneBuilder are proving too shaky — both in tooling and in native compilation — then maybe it’s time to stop patching the hammer and just let it go. After a quick (and surprisingly productive) conversation with ChatGPT, one alternative stood out: Dart and Flutter.

- Dart feels like a modern successor to Java and C++ — clean, expressive, familiar

- Flutter offers a true cross-platform UI framework that can compile to native apps or the web

Thus, I fired up some ChatGPT-generated sample projects, and got a first feel for:

- The language syntax

- UI building concepts

- Integration with IntelliJ

- Dev experience (running, debugging, hot reload)

And to my surprise: it all worked. Hot reload was smooth, the IDE integration was solid, and I was up and running much faster than expected.

Next Up: Native Compilation

The last hurdle? Testing native compilation and deployment — just like I attempted with GraalVM before. The story’s not over yet, but it’s already clear: Sometimes letting go of a beloved tool opens the door to something much better suited for the job. And this time, we built a whole new toolbox, based on DOCKER and cross-compilation.

Full Circle — And a Final Thought

After finally dropping the hammer — and hopefully not letting it land on your foot (we still need those for the DIY-pedal board) — we’re right back where we started in this chapter:

“Thinking Naively (and Breaking the Rules on Purpose)”

Remember that part where we ignored best practices just to make something run? Well, here’s the twist: Even if we had started with a pure, best-practices-first mindset — thinking in components, respecting separation of concern, and enforcing single responsibility — we would’ve likely ended up with the same architecture… but in less time.

Why?

Because good architecture often emerges when you break things down by purpose:

- Each module does one job

- Each piece exposes a clean API

- And no part depends on a specific programming language

We didn’t follow a textbook. We didn’t stick to a framework. We just built what felt right — and in the end, it looked suspiciously like… best practices.

But Be Careful

That resemblance was, in many ways, accidental. We were forced into modularity by the limitations of the toolchain. If everything had worked perfectly from day one, we might’ve ended up building… a monolith. Fast. Dirty. Fragile. So don’t assume that the “right” architecture will just reveal itself through iteration. If you’re heading in the wrong direction — and not reflecting on your pain points — you may end up in a deep, unmaintainable mess.

My Advice? Start naive. Break things. Test fast. But the moment something works — clean it up. Don’t wait until chaos sets in. Refactor early. Reflect often. And always leave the codebase better than you found it.